Ian Lindley makes the case for more accessible and interconnected green spaces in an around urban areas

With a continuing housing crisis and calls to review the role and future of green belt, we need to consider other ways to better create and integrate multi-role landscapes within and around our urban-centred populations. Long-standing complaints against green belt include:

- it isn’t necessarily scenically attractive or accessible to the general public;

- by constraining urban areas and the availability of developable land, green belt increases property prices and constrains economic development;

- it increases commuting distances for those forced to live beyond its outer edges, which reduces urban sustainability; and

- it reinforces inequality between those lucky or rich enough to live within green belt and those that do not

Green belt is seen as a constraining girdle, often inaccessible and irrelevant to many. Poor development edges, uncontrolled public access, fly-tipping and withdrawal of land management interplay to erode the quality of much green belt on its inner urban edge, and also undermine its public backing. Development that infills and rounds off the urban edges can erode accessibility to the inner boundaries of green belt and further reduce its importance to many. If green belt is to remain relevant, it needs to be part of a positive approach to its long-term management, enhancement and adaptation outside formally designated public parks. This requires resources.

The 1947 ‘Finger Plan’ for the Copenhagen formalised the use of ‘fingers’ of open space spreading from the countryside through the heart of urban areas. This approach was implemented from 1988 by Leicester City Council, in preference to seeking green belt designation, to manage urban growth. Green wedges linked with narrower green corridors provide an interconnected network of accessible, managed green space across the city. Catering for casual and formal play, recreation, education, sport, storm water management, air quality improvement and green commuting, this network includes most of the city’s remaining sites of ecological interest outside specially designated local and national nature reserves in the wider county. The network helps to improve the quality of life for residents and provides an attractive setting for new investment.

Positive management of public access and urban fringe activities is important to better supporting farmers and other landowners to cope with the pressures of adjoining urban populations, while creating opportunities for public education and involvement with land management. It should help to bring urban and rural populations together. In Leicestershire, beyond the city boundary, project coordination by the city, county and adjoining district authorities provided for round-city access along managed and waymarked byways between green wedges. Positive landscape management and its adaptation to meet changing needs can counter any decline of landscape and/or ecological value that is often associated with the urban fringe.

Where green belt may suffer continued erosion along its inner edges, use of green wedges ensures continuing proximity of green space and this its relevance to adjoining urban populations. Green wedges can expand alongside growth corridors, which in turn benefit from a range of accessible, open-space services. Development can contribute to the cost of adapting green wedges to meet the needs of growing urban populations in adjacent growth corridors. Their interrelationship provides a permanence for green space investment to counter the negative effects associated with ‘hope value’.

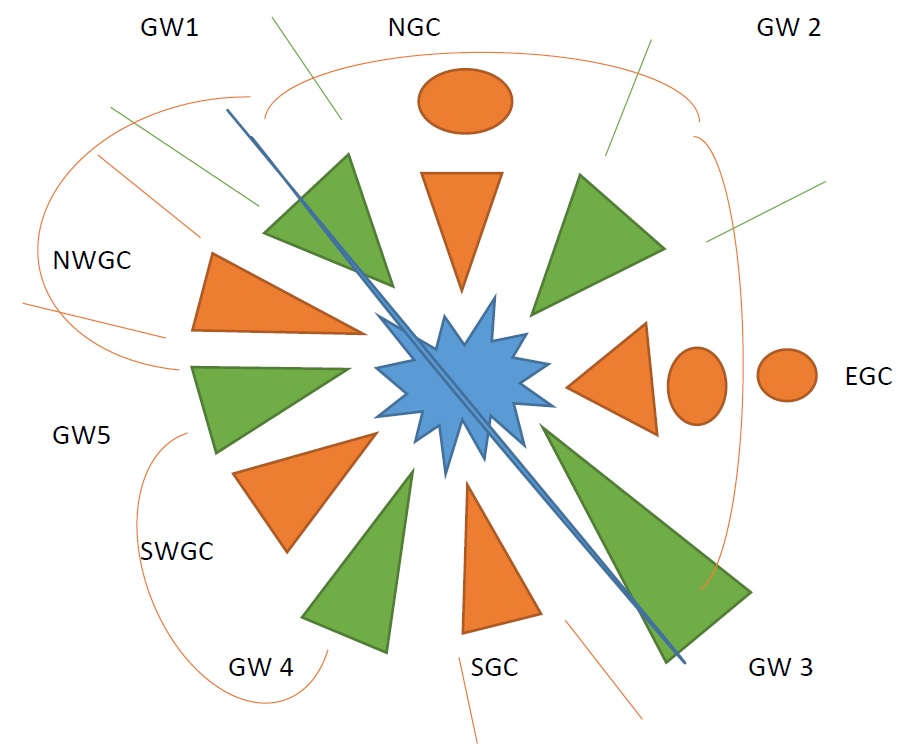

Green wedge (GW) and growth corridor (GC) plan

- GW 1 and 3 include a major river with flood retention and open spaces for ecological, landscape and recreation uses, and are linked via waymarked and managed corridors

- NGC (northern growth corridor) and EGC (eastern growth corridor) allow for planned urban expansion along public transport corridors and cater for continued separation – with inter-connectivity – between distinct fringe communities

- Future plans will demarcate the expansion of NWGC (north-western green corridor) and SGC (south green corridor) and GW 1 and 2, which are subject to current growth pressures and denoted here for strategic protection only

Use of green wedges demonstrably tackles many of the inherent constraints of green belt:

- wedges can be carefully allocated to protect and proactively manage in the long term the cherished landscape and cultural assets that society wishes to retain

- permanence encourages long-term investment and community support

- wedges do not encircle urban areas, but provide for intervening development growth and for public transport corridors

- wedges ensure continued local access to green space services

- wedge management and enhancement can be funded from associated adjoining developments, and caters directly for the needs of that population

We urgently need clarity on future positive approaches to planning for green space on our urban fringes. Green wedges provide a complementary tool for our use and lessons that could be applied to green belt if it is to continue to earn public support for its continuation.

Ian Lindley MRTPI (Rtd) MLI (Rtd) was Team Leader for Landscape and Nature Conservation at Leicester City Council from 1984 to 1991.

Thanks Ian, for starting this blog, which starts a hugely important conversation about the best ways to safeguard our treasured landscapes around London and other cities and towns, whilst allowing for necessary increase in housing and other landuses necessary to the functioning of a modern society.

As a Surrey Green Belt/ London Urban fringe native, I know that the designation of Green Belt before and after WW2 has saved vast areas of beautiful (and less beautiful, but nevertheless green) rural landscapes from being covered by the speculative builder of detached, semis and terraces and their boring roads, which were applied incrementally, but quite rapidly, and like a series of blankets, to a landscape which had been sold by auction and parcelled up within a few inter-war years, by farmers / local gentry who upped-sticks and moved to places like Somerset, where they continued to farm.

It was too late for the majority of Middlesex, and swathes of the Home Counties, now South, West, North and East London, which included many quietly lovely rural landscapes. They were replaced by areas like large areas of “Inner Outer London” — houses, roads and houses everywhere, and hardly a tree in sight. Thank God for the Green Belt

In my view, everyvillage in the green belt needs to be viable, with a critical mass of houses to support a couple of shops and pub, but one would not want to see villages expanded so quickly that they lose their identity, as many want to stay “rural”. They also might want not to coalesce with the next village– local identity even today is a potent force, rightly so in my view. It can be a nice thing to enjoy!

Turning to your Green Wedges concept, I think this is ideally suited to towns like many in the Midlands, and out of London, even Cardiff. Even London could be broken down into wedges, but I still think that this should be done for each Borough as a concept template.

I can’t help thinking that we need a “Landscape, Farm and Land use Survey” for all of the London Green Belt, and Metropolitan Open Land, conducted in areas, probably each Borough Council . It would look at landscape quality, viability of farming, and viability of current settlements, plus needs for other land uses. There would need to be panel to then review each area, comprising a group of residents, a group of Council planning officers, of Councillors, and a group of “wise outside experts” –with a Landscape architect, a farming expert, an urban designer, a development expert, and an anthropologist !

The panel would not be dominated by any one group, and it would be be charged with making recommendations as to where new settlements should go, which villages should be expanded, and by how much and over how long a period…

Pie in the sky?. Not necessarily. I think it is the way to go. Local caring residents normally feel threatened by development, and are often forced to become nimbies, and go into attack mode, to save what others (more powerful than they), want to trash. If they are part of the process, and not conveniently sidelined as happens now, they would be less nimbie and more ready to look at options.

I hope that my thoughts will be of help to developing the blog you have started.

All the best, Lewis White CMLI Coulsdon (South London)

Hi Ian

Living in Cirencester, I am privileged to live in a small town blessed with two “green wedges” that penetrate to the town core: The Bathurst Estate, to which successive Earl’s have allowed public access in daylight hours; and the Abbey grounds, bequeathed to the town by the other great local land owning family – the Chester-Masters.

I like the green wedge – or finger – concept. At EDP we try to ensure our clients incorporate these multi-functional networks into GI strategies for major urban extensions, e.g. South Worcester, North West Cardiff and Aylesbury Woodlands. So, I would simply add that any “Landscape, Farm and Land use Survey” should also explicitly include the following resources: ecology/biodiversity; water; and heritage, which will also be important to protect and enhance.

Kind regards, Richard

I agree with your approach. There is great value and potential in multi-disciplinary / professional / sector working to define how settlements can be adapted to meet future needs, not least for climate change. With existing boundaries for greenspace on urban fringes delineating the areas for attention, we have an opportunity to focus the minds of planners, landscape architects, engineers et al over the various demands that we each place on specific greenspace. Such joint work can further professional working across disciplinary boundaries. Some argue that this is provided for through the development planning framework, but in my experience that often consists of meeting the statutory consultation demands, whereby one organisation consults others on what it has already considered. We need to increasingly address fundamental questions at an earlier stage. How does greenspace currently function? How is it managed? What potential demands on its finite space exist? How can these be reconciled? How can we create multi-purpose greenspace that will meet – long term – various societal demands? The most successful examples of which I have knowledge came about by cross disciplinary groups regularly coming together to build up mutual understanding and trust. That then enabled deeper negotiation on how each could work together to better achieve each others aims – the win-win, rather than win-lose scenario. That approach worked best for community engagement as well. Occasional one off short term consultation phases seldom truly engage communities. Continuity of engagement is required, with skilled and informed rapporteur / enablers acting to coordinate community feed back. Over the last 30 yrs, despite neighbourhood plans and statutory demands to cooperate, we have witnessed the dismantling of many mechanisms, formal and otherwise, by which fundamental rethinks and engagement can be achieved. We have acquiesced in the name of cost reduction, but we lose many opportunities available, through forward thinking, to avoid subsequent costs to society from disjointed single purpose actions. In seeking to regain ground for joint working in general, the current debate over the role of metro greenbelt and its applicability in whatever form elsewhere in the UK is helpful. If we can roll that debate usefully into greenspace planning for UK towns and cities in general, then we may be able to prove the model for, and the advantages of, joint working more widely.

Picking up points you make regarding community engagement, I have personal past experience — initially very good– of some genuine community consultation, but sadly found that, once initial planning permission is secured, the useful meetings between developers, public and planners cease. Then there is no mechanism for further discussion and refinement of the design with the involvement of the resident team. The professionals go off, beaver away, and do their design job, but the only course of action left for residents to input into the final design is to object at the detailed Planning Application. The chances of getting justified changes at that stage are pretty much zilch.

I have personally spoken at a Planning Committee as an objector (as a member of the public) , prefacing my 2 minutes allotted maximum with the words ” Due to the adversarial way the UK planning system works, I find myself having to object to 20% of the design, but actually very much support the other 80%. ” In a better scenario, I would have been able to sit down with the designers and planers and other residents to explain why I was unhappy and be empowered to pose an alternative solution to the 20%. As a there was no mechanism to do this, I couldn’t, and had to let it go. That is the problem– there is no statutory forum for detailed public input or proposal of alternatives or modifications

You mention that over the last 30 years, many useful mechanisms have been dismantled. This reminded me that in the 1980’s I had been involved in a public Inquiry ( as a local resident) where the inspector allowed the residents a good amount of time to explain their views on the proposal, which was not only a good example of the democratic process in action, but I think resulted in a fairer, better result. I wonder if this would have happened now, had the same proposal arisen. I have more recently witnessed the charade of an “Examination in public” regarding a major project where the poor old public were grudgingly given a micro minute to put their views as to the total absence of alternatives to the proposal. The Inspector was very aggressive to the public, and then presided over a discussion of minutiae between the well paid professionals. The whole affair was a sad commentary on how the public were given no opportunity to come up with an alternative scheme that they the public are paying for over the next 20 years! How badly the democratic process has been served.

Cost reduction in Planning, 2017 style, starts with the fact that most planning authorities no longer write a simple standard informative letter to the immediate neighbours when someone puts in a Planning application. A notice gets fixed to a nearby lamp-post,, but as we know, that notice can get torn down in minutes by a passing yob, or….the applicant.

If we can’t ensure that the neighbours are properly informed by the Council spending a few pounds on a standard letter , envelopes, and stamps, and for an admin officer to stuff the 2 or 3 envelopes and put them in the post out” pigeon hole, how on Earth are we going to get the wounded/ broken Planning system cured, and the new mechanisms you are posing, in place?.

Can’t disagree, but we do need to ensure that Govt realises that by better engaging all interested parties in more continuous dialogue, (not just at plan app stages) we may create better informed decisions, better support elected reps in their roles and produce more multi-benefit outcomes than one party wins and others lose type equations. But in the current climate that is asking a great deal more than I think the vested interests that create our systems will support. So let us focus on ensuring that Green belt is re-framed to meet societal demands (such that the concept of green space planning / protection / management / enhancement and creation – for those multi uses- is reinforced & not sacrificed to the latest economic crisis). Let us also try to roll out appropriate green space networks for most of our main settlements, and use not just GB but other approaches such as Green Wedge that can also be underpinned by the same methodology as outlined in my first piece. Viz – assessment of genius loci, leading to multiple green space function designations, (ie mutually supporting labels on plan the green space elements of devt / settlement plans) that can mutually support the essential retention of green space & help to focus joint working between all ‘stakeholders’.

Hi again Ian, apologies for delay in responding.

It seems from what you say that we need a genuine “Landscape plan” for each Borough, which would of course have to relate to the adjacent ones, to ensure a co-ordinated approach. It cannot be separate from a Development plan, to ensure that the new development is placed well, and does not compromise the viability of farming, and sits well in the landscape.

Driving past Heathrow recently I was looking over the remaining wistful landscape of hedge-less and treeless wheat fields , probably in Hounslow, or Spelthorne, and mentally posing some options –should it be dug in part for gravel to make new lakes, with part of the land redeveloped as a garden village, and part kept as grazing land?. Or should it be kept as wheatfields, and enhanced with new copses and hedges. I wondered what made best use of the land and would create the best landscapoe overall for current and future generations.

Who do you think should look at these options ? Planners alone, planners plus councillors, developers, public?. Who is or are the Public? Do the borough councils have the necessary landscape design expertise?

I wonder if a pilot project could be sponsored by the GLA, eg to look at the SW London Boroughs with Green Belt , (Croydon , Sutton, Kingston ) although it would have to include Surrey and the adjacent Surrey district councils . Ditto NW NE and SE.

What about MOL. Some MOL looks just like Green belt. Need to look at MOL too!

Lewis

I’m coming to this rather late, but as part of some wider work I have been looking at accessible natural greenspace around Leicester and Leicestershire.

In contrast to Birmingham, Derby, Coventry and Nottingham, all of which have considerable and consistent provision of larger accessible natural greenspaces around their cities, Leicester has virtually no provision of larger greenspaces other than in the northwest.

My theory is that the green-wedge policy has led to comparatively greater fragmentation of larger greenspaces in comparison to greenbelt policies.

In the northwest of Leicester the landscapes of Charnwood and the National Forest have effectively protected the integrity of larger greenspace landscape units as a greenbelt policy may have done.