UK Student Travel Award-winner, Emma Beaumont (University of Sheffield) shares thoughts from her recent trip to Greenwich Millennium Village to examine the transformative effects of landscape.

From the outset, the aim of Greenwich Millennium Village has been to provide in excess of 3000 homes, commercial spaces, social and community facilities, along with an ‘eco-park’ in the heart of London. The development of the site, a 121-hectare former gasworks that was once the largest in Europe, began with a competition launched in 1997. This sought to encourage the creation of a high-density, mixed tenure housing scheme. Work commenced on the winning scheme in 1999 and is still ongoing today, based on a model for ‘sustainable development’.

The objectives of Greenwich Millennium Village are described as: “The promotion of mixed-use development to create linkages between different users and create more vibrant places” with a purpose to “achieve social inclusion through the establishment of a homogenous community with an emphasis on the public rather than the private and a mixture of uses, a variety of types of tenure and sustainable residential densities, and an animated public realm“.

Having studied sustainable housing design, I have developed a strong interest in socially responsive urban design and I am curious to understand how the design, linking, and sculpting of spaces can influence the way people behave and interact with one another. I want to understand more about how design can help to create a strong community network. With this in mind, I went to visit the village to analyse first-hand to what extent I believe the objectives of the development have been achieved on such a high profile project with the aim of achieving social sustainability.

Greenwich Millennium Village (GMV) is one of the most well-known examples of large-scale urban regeneration in the UK. The concept of transformation through urban regeneration has become incredibly topical in recent years, especially with regards to sustainability. Particular elements of concern often include; public health, community building and environmental protection. GMV was a cutting edge development at the time, that ticked all of these criteria boxes for achieving sustainability.

The obvious transformation of this area of the Greenwich Peninsula from a thriving industrial centre, to derelict brownfield by the 1980s, eventually becoming a “vibrant”, mixed-use residential area with its own ecological park is something that fascinated me. But on top of this, I was interested in determining further changes that have occurred since initial construction, particularly in the areas that were built first, with regards to social sustainability and inclusion. Has this time, combined with effective design, allowed for the establishment of a strong community?

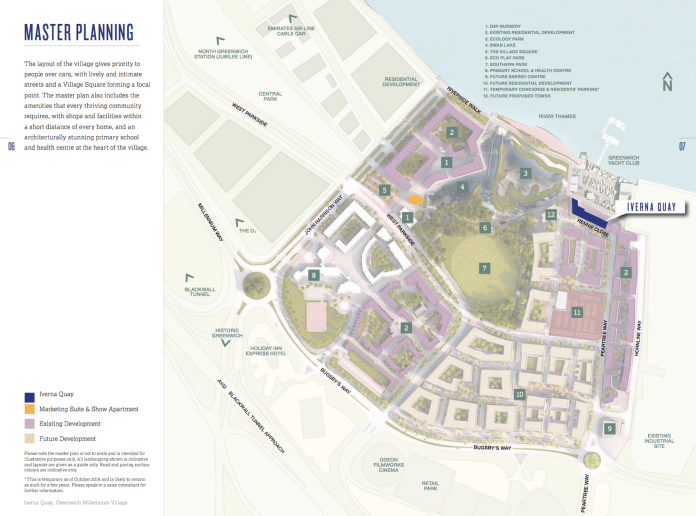

The aims of GMV, with a more specific focus on socially responsive design and community creation, included an emphasis of public over private spaces, with “lively and intimate streets and a village square forming a focal point“. A mixture of uses (commercial, social and communal) with facilities a short distance from every home and mixed-tenure aimed to create a diverse and inclusive community where social interaction is facilitated and encouraged.

My previous landscape architectural studies, specifically those focused around urban regeneration that seeks to enhance pedestrian experience and the study of sustainable housing design, with a personal focus on community creation, have informed my analysis. Such studies, along with additional reading, have provided a foundation from which to critique the success of the GMV building massing, sculpting of space, and allocation of space to communal facilities in an attempt to create an inclusive and strong community network.

I now have an extensive “toolbox” of things to analyse and criteria to look for when determining the quality of urban design in creating a more sociable experience for people. Examples include: prioritising pedestrian experience, paying attention to the transitional gradient between public through communal to private spaces, providing protection, comfort and visual interest to spaces as well as activating edges to encourage staying. The number of people staying in an urban space is an indicator of its quality, and staying is a facilitator of social interaction. There are a number of types of interaction, from passive (being alone in the presence of others e.g. people watching) through fleeting, to enduring. All of these are vital in the creation of a strong community.

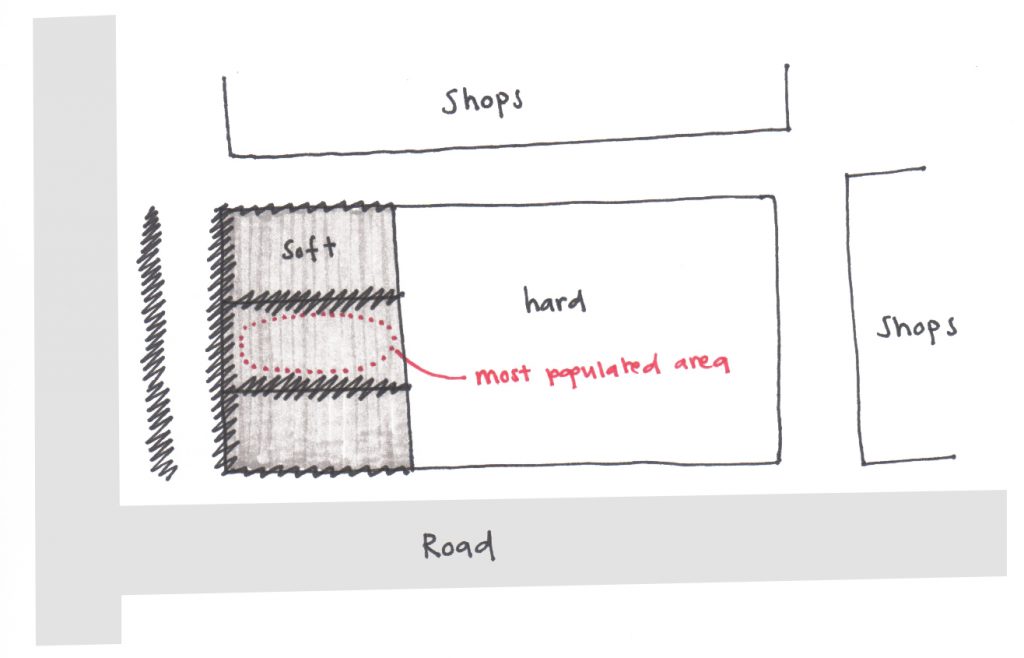

One of the overall social aims of the project was an animated public realm with the ‘village square’ as a focal point and centre of activity. This was the first part of the village that I reached when I arrived, having walked from the tube station. The rectangular courtyard is enclosed by shops and communal facilities on two sides and then by crossroads on the others. It is split into hard and soft areas, with the soft then being divided again into three ‘pockets’, by vegetation. Overall, the shops and café seemed to be well used but the square itself was mainly used by pedestrians crossing it, not for staying.

The hard-surfaced area was particularly empty, which may be the result of a lack of seating or resting places combined with the exposed nature of the space. There is no barrier between the space and a busy road. Street trees would be a simple solution to this, acting as a more permeable barrier and providing a level of enclosure, making users of the courtyard feel safer. It would also aid in addressing issues of both noise and air pollution. The level change and steps around the edge are a wasted opportunity and could have been designed with seating as a dual purpose as well as being better integrated with the adjacent shops. A more permeable transition from the interior to exterior of the shops and into the courtyard space may also encourage use and thus interaction between users. One café has attempted to do this by placing seating outside but then have erected a barrier around it, which only segregates users from the space and others using it.

The soft area of the courtyard was used significantly more during my observation time. The most used of the three “pockets” was the central one and I am sure that it is no coincidence this is the most sheltered of the three spaces. Shelter and enclosure combined with explicit seating opportunities, in the form of benches, encouraged people to use these spaces and stay in them. This affords all types of social interaction to then occur. Designing to encourage social interaction seems to have been more successful in the soft, planted side of the village square.

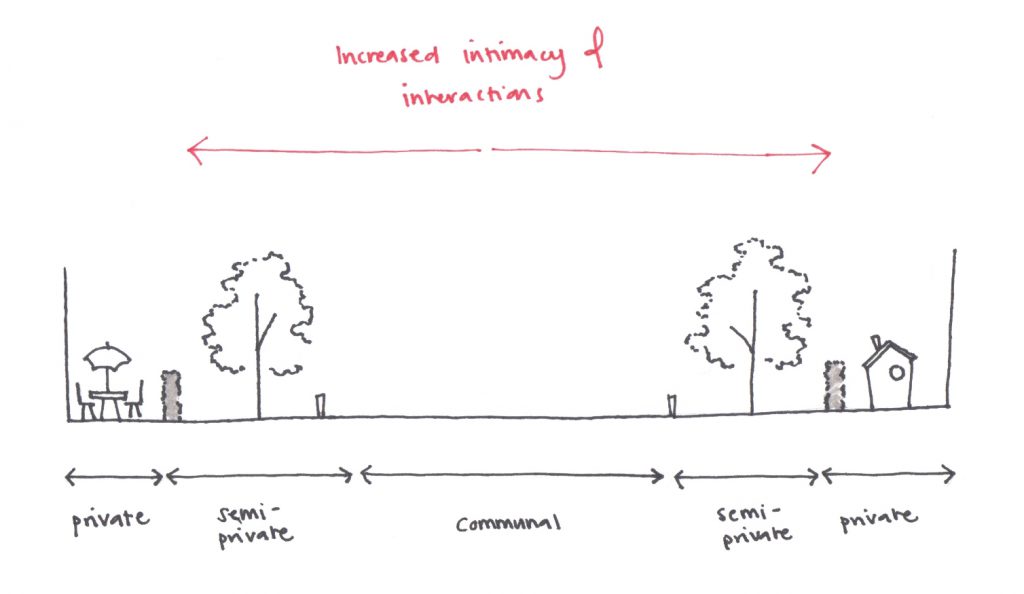

Another aim of GMV was an emphasis of public over private spaces. The relationship and transitional gradient between ownership of spaces is something that must be carefully considered in effective design to encourage interaction and to help build a community. Despite it seeming counter-intuitive, it is important that not all spaces are completely publicly accessible when designing for community so that residents experience interaction at different levels of intimacy too. Street trees are particularly effective in creating a transitional social gradient as they are a more permeable boundary marker and they can provide shelter, enclosure, seasonal interest and even play opportunities as well as subtly defining ownership of space (see Fig 3). Although, the resulting experience is dependent on the species and maturity of the tree, and can therefore evolve over time.

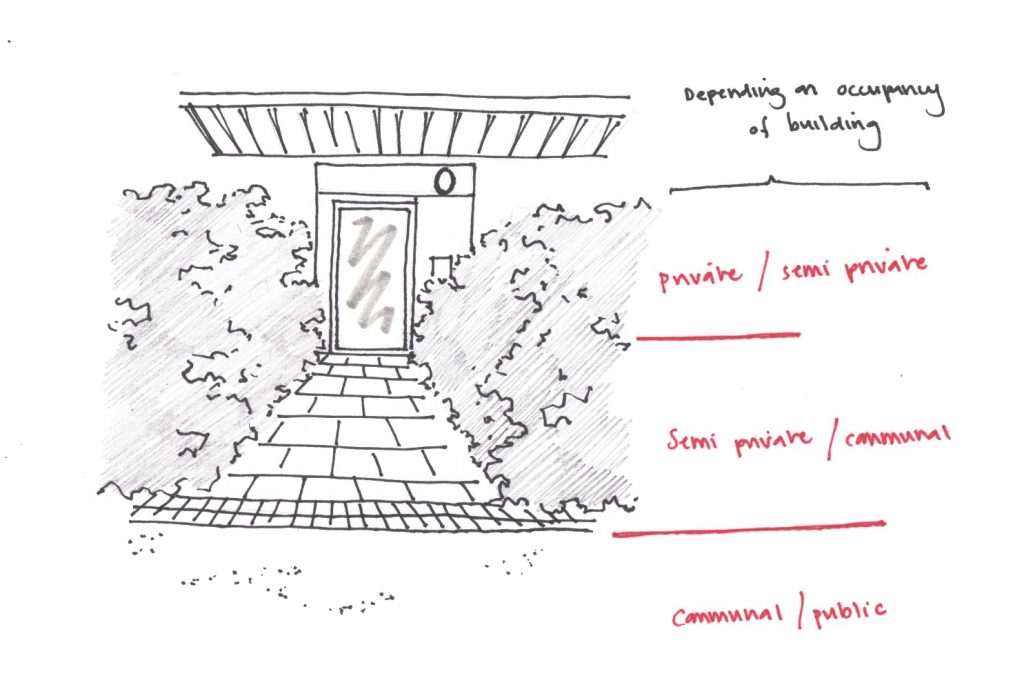

Surface materiality is another method of defining ownership of space in a subtler manner, for example, smaller sett sizes of paving are often used to indicate more private areas (see Fig 4). In the residential streets throughout the village, it is clear that these design intentions are there, however it seems to have worked more successfully in some areas than others. This is predominantly down to residents themselves and how they choose to take ownership of spaces.

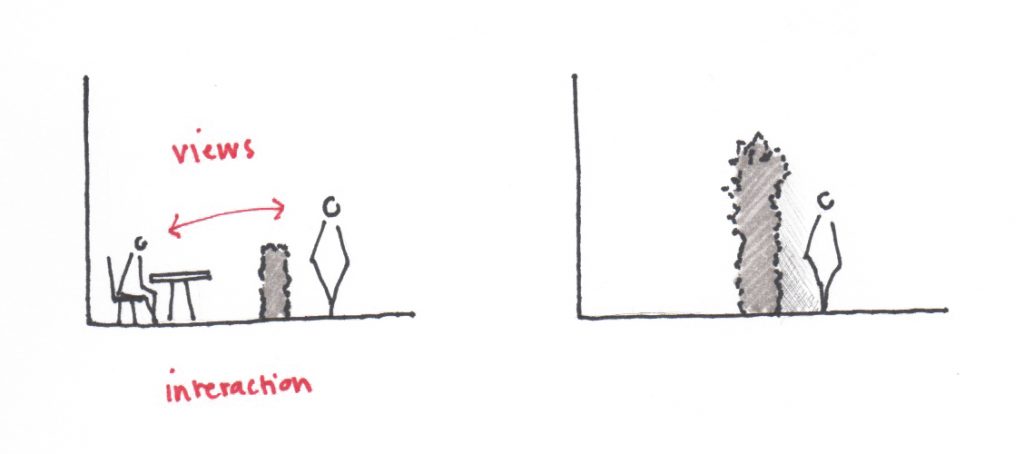

For example, where hedges surrounding private gardens have been neglected by homeowners and allowed to grow over 2 metres tall, this creates a harsh boundary between the gardens and the communal space adjacent to it, with no views in or out. Whereas when hedges have been maintained at a lower height, there can still be interactions of all types between homeowners and neighbours or pedestrians. Design can give users the opportunity for personalisation but therefore is often reliant on how they take ownership of the space as to whether the design aims are achieved (see Fig 5).

As is common with many community-orientated housing projects, the buildings are massed in a way that creates central communal courtyards within each block (see Fig 1). These are semi-private spaces that can only be accessed by residents of the particular block, locked by very severe looking steel fences. So, this means I couldn’t access them to conduct any form of analysis. From what I could see, they do look well designed with plenty of opportunities for play, staying and interaction through providing enclosure, a range of vegetation types with seasonal interest, seating and play equipment. It also seems to be the case that all ground floor residents have direct access onto the space, through French doors at the back of each property. These semi-private spaces allow smaller, stronger sub-communities to develop between residents of the same block.

As they are gated, parents may feel more reassured in allowing their children to play out on their own, and make friends with other children. These kinds of interactions could ensure a lasting community that would grow stronger over time, through the children. However, there is a counter-argument for this kind of exclusivity. Locked gates can increase feelings of security, but they could, in fact, do the opposite. They may imply that there is a reason for residents to feel unsafe if they weren’t there, which does the opposite of creating an overall feeling of strength in community throughout the ‘village’. They also exclude residents from other blocks, or even members of the public from these spaces, which completely contradicts the aim of “an emphasis of public over private spaces”.

Conversely, it could be argued that the large public park serves this overall purpose of amenity space for all residents and members of the public, where interaction between all groups is facilitated. Even with the weather being overcast on my day of observation, the park was very well used. It is very naturalistic and “wild” in terms of planting, which was surprising to me for somewhere so close to central London. This attracts wildlife, which in turn attracts people, allowing for interactions to occur. There is so much evidence to prove the relationship between contact with nature and improvements in physical and mental health, and in the words of GMV’s mission statement, a “healthy community is an inclusive community“.

The park is well integrated within the residential areas and is easily accessible for residents. Transport connections between the village and the wider area of London are strong, with many bus stops and the underground station a short walk away. There are other developments of a similar style increasing in number around the village, but most seemed to be higher density. A compromise that needs to be carefully considered is catering for the ever-increasing need for affordable, high-density housing, and designing for healthy and inclusive communities.

There are some areas surrounding the site that remain as industrial brownfield and have not yet seen the same transformative regeneration of the rest of Greenwich peninsula. Walking along these perimeters of the village, it felt very isolated and even unsafe. With the rate of development, this will probably not be an issue in the coming years, but with any new development, it is crucial that the integration between the two, particularly in terms of facilitating social interaction and creating communities is considered.

The River Thames runs along the northern perimeter of the site and the park, an opportunity that I think has not been taken as far as it could have. The riverside apartments seem to have become very desirable and exclusive places to live, which doesn’t fit with the original inclusive ethos of the village. There is a walkway along the riverfront, but a fence between both the park and the path and the path and the river. Instead of a transitional space from the park through to the river, that facilitates all types of interaction, it is closed off and uninspiring. I recognise that there is an issue of safety that needs to be contemplated, but design solutions that encourage interaction in a safe manner could be possible. A successful case study for riverfront design that could inspire such a transformation is the Chicago Riverwalk by Sasaki. The goal was to embrace the river as a recreational amenity and to form new connections to the water’s edge.

Creating spaces that encourage interactions between people with each other as well as the water was the primary focus of this project and therefore is something that I believe should be applied to GMV, if it’s aim is social sustainability. I did witness some children playing on the beaches at the water’s edge, and there is even a makeshift sculpture that has been built from objects washed ashore. This proves that residents do want to make use of this connection, even if design doesn’t currently facilitate this as much as it should. The Greenwich Yacht Club sits along this same stretch of river but its entrance is gated and locked with barbed wire fences. This could be an opportunity to involve the community with the club and strengthen relationships through the use of the river for recreation and amenity. However, the exact opposite impression is being given out with such a harsh and unwelcoming threshold between the two.

In terms of the overall ‘village-like’ quality and feeling of strength in community of the development, there are both strengths and weaknesses. Some streets felt to have more of a community presence than others. This is immensely down to personalisation, and the level to which residents decide to claim ownership of the spaces outside their houses. As previously mentioned, design can allow for personalisation, but it is up to residents as to whether they take this opportunity.

Other factors are also responsible too, however. The width of the street also had an impact; too narrow and there was no transitional gradient of ownership of space, too wide and they felt exposed and overwhelming. Enclosure, provided by other buildings and by street trees, has an effect on the experience of intimacy within a space. Those streets with the most mature trees, which provide the most enclosure, felt to have more of a community presence. Too much enclosure, however, as a result of taller buildings, can have the opposite effect by towering over and overpowering the street space.

Most of the blocks within GMV are mid-rise, so it is less of an issue overall. This is unusual for developments so close to central London, where density is prioritised. The location of the street within the framework of the village also seemed to play a part, with those on the perimeter feeling more isolated.

Whilst conducting my observations, I kept seeing the same group of children all afternoon. They were going in and out of a ground floor apartment, where a mother had left the door open. This action increases permeability from inside the home, out onto the communal street. The design of the street and the established feeling of community obviously allowed her to feel comfortable enough to leave the door like this and to let her children go and play. The children were seen playing in the streets, in the courtyard spaces (even the ‘empty’ ones with no seating or equipment) and along the river bank. I think these acts are unusual for such an urban location and prove that GMV is successful in designing with community in mind.

The level of personalisation of streets (although differing from residence to residence) was higher than I have seen anywhere else in the city. It is through design that users feel able to do this, and this action helps in encouraging interaction between neighbours, allowing a community to form. It was higher in the areas of the development to be constructed first, which supports the idea that this time has given the community a chance to build strength.

In conclusion, I think that the design of GMV does successfully consider social sustainability and the creation of a strong community. My analysis of the development has reinforced the reliability of urban design principles I have learnt in my time studying Landscape Architecture. There are a number of aspects however, that I don’t think are designed with social interaction in mind.

- The squares and courtyards throughout the development should be “hubs” of social interaction that are above the communal residential streets in the hierarchy of interaction.

- They should be livelier than the streets and offer opportunities for staying, such as shelter and enclosure, seating or informal rest spots, play equipment etc. All of these encourage people to stay and as a result, interact with one another. This is a particular issue in the ‘Village Square’ which is supposed to be the ‘focal point’ of community activity.

- Permeability between the shops and businesses and the square needs to be introduced, as does shelter from the busy road.

- More opportunities for rest which encourage staying also need to be provided.

- The inaccessibility of the semi-private courtyards within blocks to anyone but residents is a controversial point for discussion. On the one hand, it allows for the creation of closer, sub-communities. However, the gates add an element of exclusivity which contradicts the communal ethos of the development.

- Finally, I think something that has been crucially overlooked in the socially responsive design of the village is the river. Connections between people and the river for recreational use are an obvious facilitator for the formation of connections between the people themselves. At the moment these connections are virtually non-existent.

This research has confirmed my beliefs that it is essential that the disciplines of architecture, urban design and landscape architecture work together in a complementary way in the creation of socially responsive spaces in order to achieve happy, healthy and strong communities. To do so, we need to design to facilitate all forms of interaction wherever possible. However, we need to understand that the effects may not be immediate and that time needs to be allowed for a strength in community to develop and transform. This element of longevity needs to be taken into consideration as part of such design decisions.

Thank you for a thoughtful analysis of a place I have often passed by and sometimes explored. There are good things about the Millennium Village but also many disappointments. Thinking of Ian Thompson’s book ( Ecology, Community and Delight: Sources of Values in Landscape Architecture: Sources of Value in Landscape Architecture) I would say that of the three sources of value the treatment of Ecology is the most successful and that of Community the least successful. As you say, the gated internal courtyards have a logic but also a degree of social ambiguity. Similarly, the relation to the river is a wasted opportunity. The beach sculpture in your photograph has been there for perhaps 15 years so I think someone must be caring for it. The Ecology Park is a good place for birds and plants, and a pleasure to walk through, but if I was a child I would not want to be cut off from its wildness by decking and fences. Re the balance of community and privacy, I wonder if you know the very interesting book by Serge Chermayeff and Christopher Alexander (Community and Privacy: Toward a New Architecture of Humanism Paperback, 1963). They wrote as architects but their subject is ‘really’ landscape architecture. A vanishingly low percentage of architects are good landscape architects. Far too many architects think they can ‘do’ landscape architecture but, probably because they don’t know what it involves, are completely at sea with it. The re-development of the whole Greenwich Peninsula in the past 20 years is a perfect example of this truth. They should have begun with a landscape plan and it should have been based on the principles of landscape urbanism.